When the Smith family waved goodbye to six of their sons who went off to fight in WWI, they feared they’d never see them again. For five of their sons, that was the harsh reality.

These events closely resemble those of Steven Spielberg’s WWII epic, “Saving Private Ryan,” though they happened 70 years before the film, during WWI.

The Smith Family

Margaret and John Smith’s two years of hell began in September 1916 when their 22-year-old son Robert was killed in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, on the Somme. Robert died just 11 weeks after arriving in France and he had been among 100 men who had wrongly been told the Germans were retreating from their position.

WWI

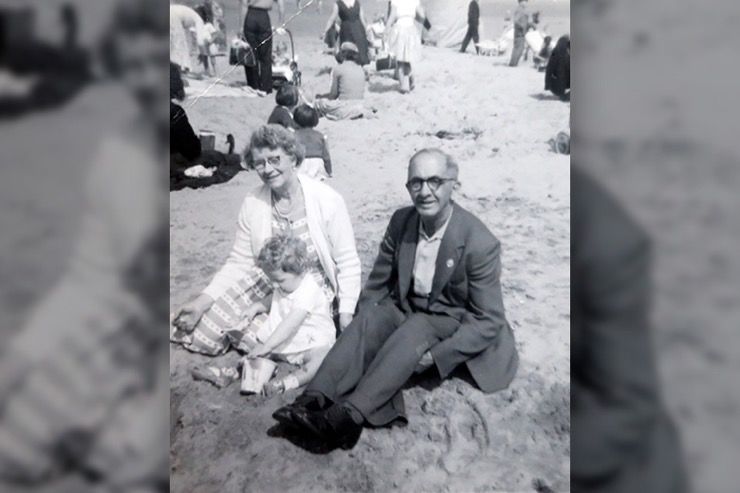

Margaret, a mill worker, and her husband John, a chimney sweep, had 11 children, with six being sent away to fight in WWI. She feared that they would never return, saying to a news station, “Don’t have boys, they’ll only end up as cannon fodder,” as reported by The Sun.

Robert Smith

Robert lost his life on the morning of September 16, 1916, when he was hit by enemy machine gun fire. He was then taken to a casualty station, where at first, he and his older brother George, 26, who was in the same battalion, joked together. But three days later, Robert died from his wounds.

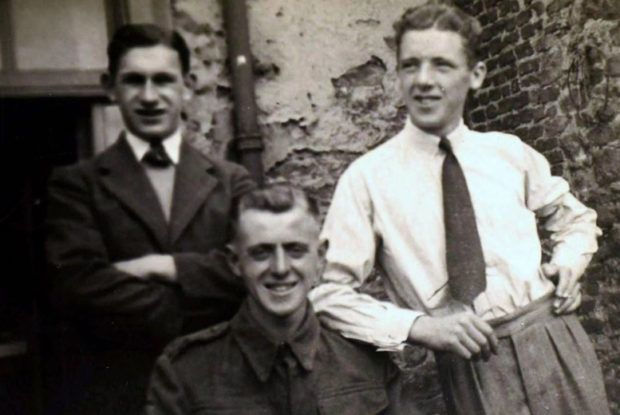

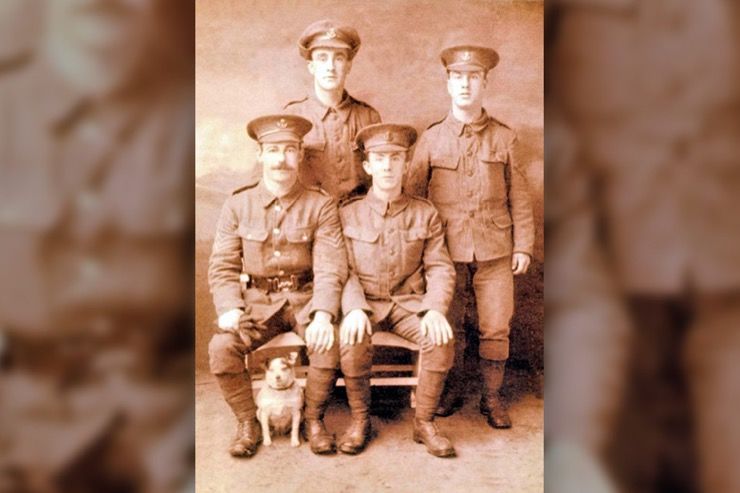

Four Brothers

After his death, four brothers – George, John, Frederick and Alfred – came home on leave and posted for a photo, which wound up being their last one together. The sixth son, Wilfred, was not in the photo, because he wasn’t called up at the time.

George Smith

On Bonfire Night 1916, George lost his life when he was shot through the head by a sniper as he walked down waist-deep mud. He body disappeared under the surface, only to be lost forever. Then, Frederick, 21, was wounded on Christmas Eve 1916 and was sent home to recover where he remained until February 1917.

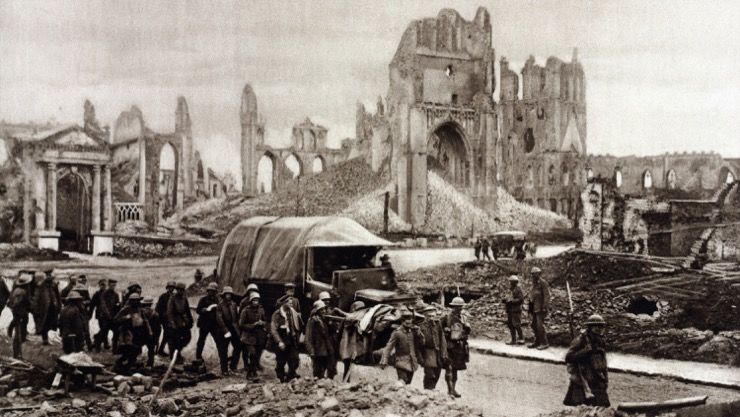

Third Battle Of Ypres

The following week, Wilfred joined his brothers, and five months later, on the opening day of the third battle of Ypres, Frederick was killed. Frederick has no grave but his name is shown on the Menin Gate in Ypres. Then, there was the fourth brother, John Stout, 37, who was married with two daughters.

The Nightmare Continues

He was killed in the war on October 9, 1917, and his body was never found. The nightmare only continued the following summer, when their fifth son, Alfred, 30, was wounded in a battle on the Ardre river. He died of his wounds at a military hospital on July 22, 1918.

Margaret’s Heartache

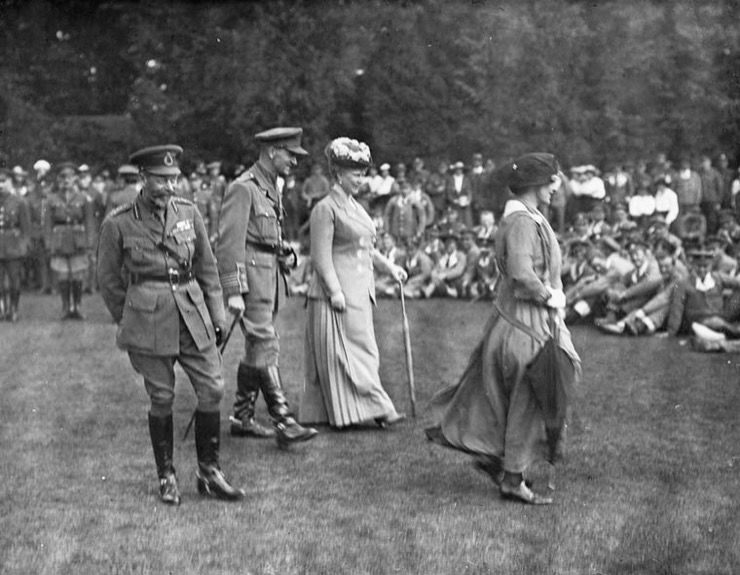

Just three weeks later, Queen Mary received a letter begging her to end Margaret Smith’s heartache, and bring her last son, Wilfred, home. By that time, Wilfred was 20-years-old, and he had fought the Germans in the trenches of Ypres.

Black-Edged Telegrams

Margaret couldn’t handle receiving one more telegram, after receiving five black-edged telegrams from the War Office, each one confirming that one of their boys had died. Three of her sons were never found and to this day, their bodies still lie under the fields of Northern France and Flanders.

Queen Mary

Then, in August of 1917, Queen Mary, the wife of King George V, read Margaret’s horrible story in a letter sent to Buckingham Palace. She vowed in the moment that Wilfred would be returned home safe to his mother from the front line of war.

Wilfred Smith

To Margaret’s surprise, a few days later, the Queen’s private secretary, Edward Wallington, wrote back to her saying Her Majesty had contacted the War Office to find Private Smith in the trenches and order him home. During his time at war, Wilfred survived mustard gas attacks and was training for the final round of combat with enemy soldiers.

Returning Home

It was then that a messenger arrived to the French-Belgian border of Terdeghem, with orders from Army headquarters for Wilfred to pack his bag and go home. Military historian John Sheen, an expert on the Durham Light Infantry, said “Mrs. Smith’s story must have touched the Queen’s heart because taking a man from the line for personal reasons is extremely rare,” as reported by The Sun.

Suffering After The War

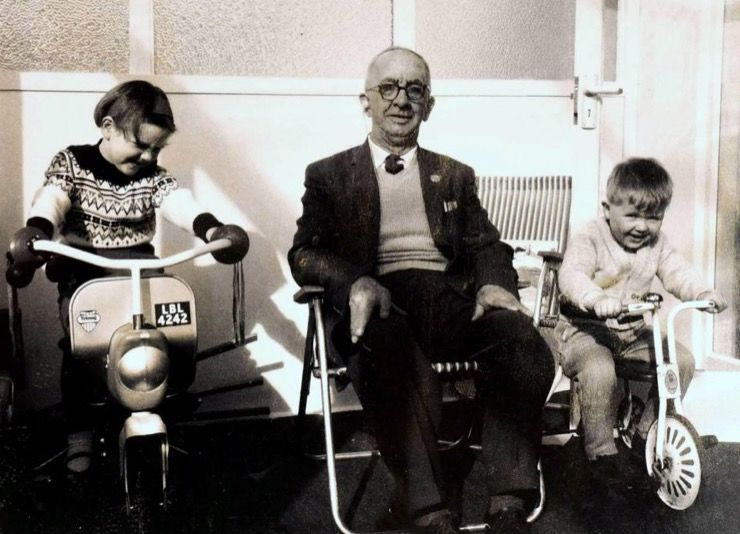

After Queen Mary sent Wilfred home to Barnard Castle, he became a stonemason and chimney sweep, like his father John, who died in 1918. Throughout the remainder of his life, Wilfred suffered chronic chest problems from the mustard gas attack, and he lived until he was 69-years-old, having raised five children with his wife Hannah.

Barnard Castle

Wilfred’s granddaughter Amanda, 52, said, “As children we knew a little bit about Wilfred’s amazing story. My mom would tell us some of it but Grandad did not really talk about it. I think it was probably hard for him in some ways, as he was lucky to leave the war behind – though the people in Barnard Castle didn’t see it that way.”

Memorial

“Few people can imagine what it must have been like to him to lose five brothers,” Amanda added. On a Sunday in November 2018, Wilfred’s daughter, Diane, 74, along with Amanda and her daughter Charlene 30, son Craig, 28, and grandson Tommy, 2, planted poppy crosses at Barnard Castle’s war memorial.

Mary Bircham

It is there that the names of the five brothers are remembered. Anna recalls that Wilfred was brought home in the first place thanks to a woman named Mary Bircham, who befriended Margaret at the time of the war. It was Bircham who took the brave step of writing Queen Mary and begging her to save Margaret from any further sadness by bringing Wilfred home.

Saving Private Smith

Anna said, “We owe a lot to Mrs. Bircham, because without her, none of us would be here. Wilfred was sent home to keep the family name alive, and he was able to live a long life because of that.” With the help of historians, The Sun has pieced together this story of Saving Private Smith.

Saving Private Ryan

While much of the 1998 movie “Saving Private Ryan” was inspired by fiction, the premise behind Captain Miller’s mission is based on a true story. It covers the story of the Niland brothers – Preston, Edward, Robert, and Frederick – from Tonawanda, New York serving in WWII.

Similar Stories

When the War Department learned that three of the four brothers had perished, they decided the remaining brother needed to be brought home, just like it was portrayed in the film and for the Smith family. The only difference is the Smith brothers served in WWI.

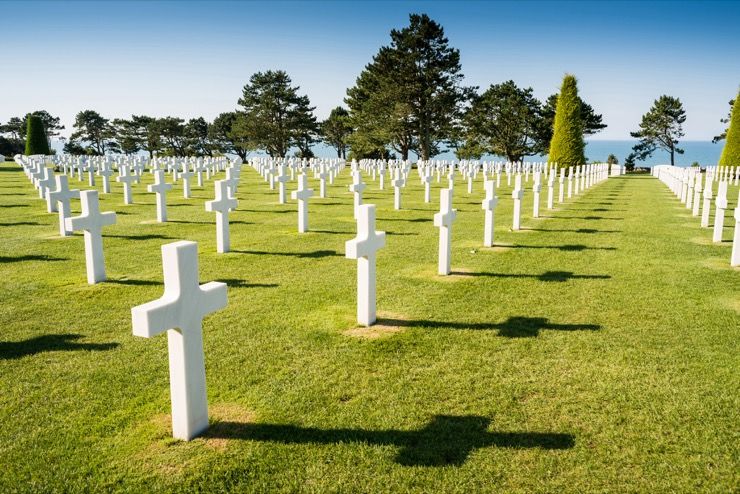

Niland Family

The fourth Niland brother, Frederick, was ordered home to the U.S. in 1944. But, something unexpected happened in May 1945, when the Nilands received news that Edward was found alive in camp when it was liberated by British forces. The two other Niland brothers, Preston and Robert, were buried side-by-side in the American cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer.