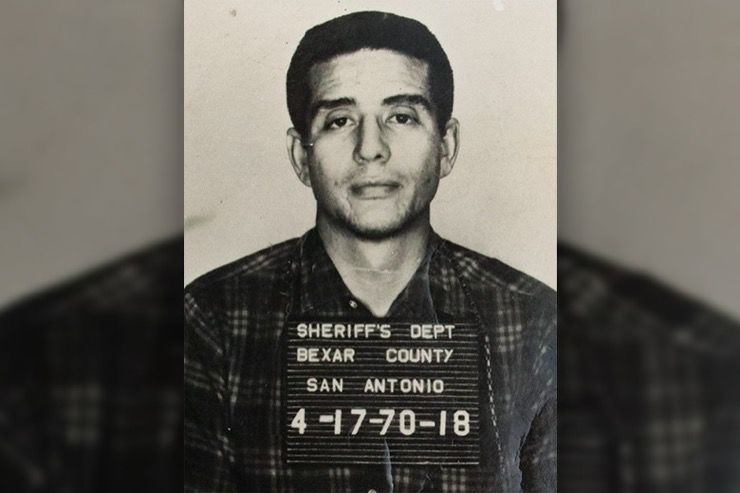

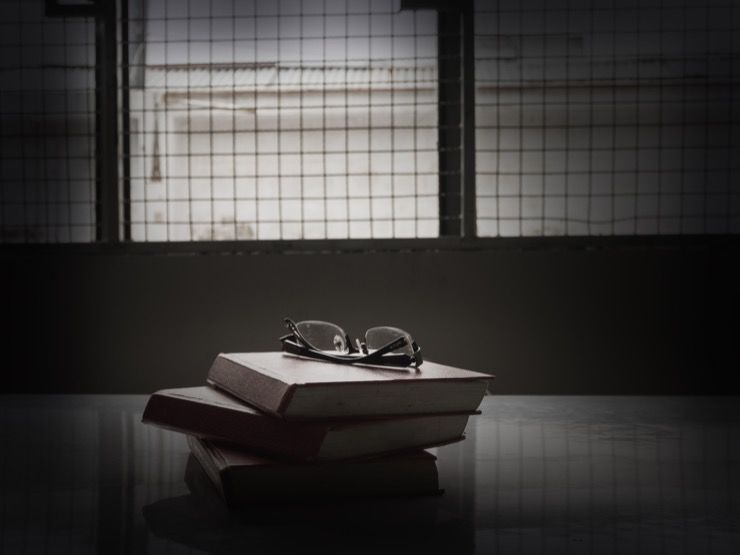

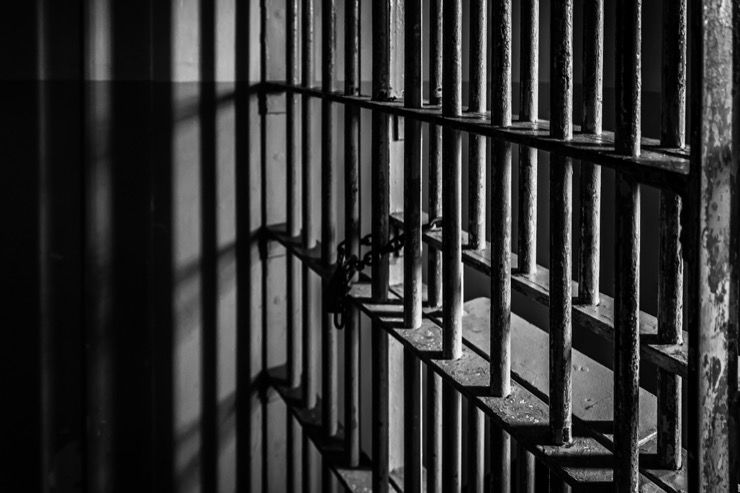

Fred Cruz sat in the darkness so deep and dreadful that it made his eyes ache. He shrugged the threadbare blanket he’d been given over his shoulders and looked at the hole on the floor that served as his toilet. Taking a bite of his three meager slices of bread, Cruz worried that he’d finally go mad this time around.

Cruz had been in solitary before, but two weeks in the hole was something even his determined attitude could hardly bear. He looked at the scant rays of light under the door, alone with his thoughts, and wondered when they might let him out. He still had a long way to go.

Days in Darkness

Cruz’s current stretch of solitary took place in the sixth year of his fifteen-year sentence. He had been put in prison for robbery but he’d gone into solitary simply because he didn’t like authority. More than that, he wasn’t a big fan of arbitrary rules; a favorite of the guards in the East Texas prison in which he’d found himself incarcerated. Still, Cruz was tough. He could outlast this stretch like he’d outlasted all the others.

Family Business

When Cruz was young in the early sixties, his father had abandoned the family. Growing up in the segregated Mexican-American barrios on the west side of San Antonio, Cruz had to learn to be tough. Members of his family sold drugs to survive and many of them, Cruz included, had frequent run-ins with the police. His brother Fred was even shot dead by police. Finally, a sloppy robbery landed Cruz himself in the slammer.

Arbitrary

Cruz’s most recent stint in solitary was due to him being hauled in and punished for a still-unknown indiscretion that was allegedly against prison policy. Or rather, it was because he chose to question this ambiguous slight instead of just taking the punishment. He insisted he was entitled to a fair hearing; but that was his first mistake, thinking he was entitled to anything but abuse.

Law Studies

Cruz decided from that moment on to dedicate his time in prison to something greater than himself. He was determined to study law while he was in there. He ignored the siren song of heroin, marijuana, and prison hooch and instead devoured textbook after textbook. He read the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and countless Supreme Court cases. Of course, the higher-ups didn’t like that.

Dim-Witted Criminal

At this point in his prison tenure, most of Cruz’s record indicated him as little more than an eighth-grade dropout with an IQ of 87. He was considered an “extremely poor prospect” for rehabilitation. Those descriptions were quickly disproved when he began studying law. A subsequent profile by a clinical psychologist indicated that he was intellectually bright, suspicious, prone to be hostile to authority, and possessed leadership potential.

Court Writer

At first, Cruz focused on appealing his own case on the grounds of inadequate representation, which given the time period, was probably the case. The lower courts, of course, dismissed Cruz’s pleadings, but his fellow inmates soon looked to him as someone who understood the complexities of the legal system. He soon helped them with their own appeals.

Helping Others

Cruz’s altruism was looked down upon by the prison administrators. Helping other prisoners and keeping legal books or documents in one’s cell were both against the rules. It was forbidden even to talk to another prisoner about the law at that time. Cruz did so anyway, heedless of the eventual time he ended up spending in the hole.

Not Deterred

Eventually, the days in solitary turned into weeks, then months, and finally years. In the end, he didn’t care. Cruz kept on doing what he could to increase his legal acumen and that of his peers. He soon became the most dangerous man inside the Texas legal system, not dangerous to other prisoners, but to the system itself. And those who punished him for expanding his knowledge would eventually be punished themselves.

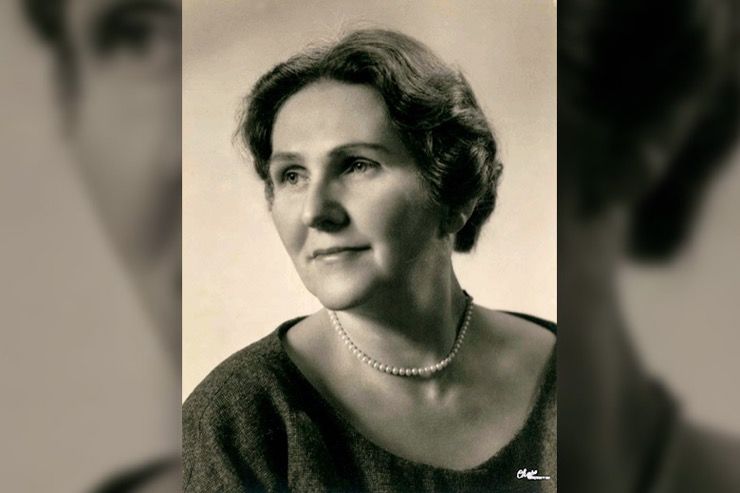

Mrs. Jalet

First, though, Fred Cruz had to meet Frances Jalet. Born in Boston, on the other side of the country, one would never have imagined that the Columbia Law School graduate would have ever associated with a man like Cruz. Jalet was a rare thing in those days, an educated woman and working mother-of-five. It was a lethal combination and her tenacity in both her marriage and career would set the tone for her extraordinary life.

Mad Husband

In 1956, Jalet’s husband barely survived a plane crash and came home with a severe brain injury. The injury changed him entirely and he soon fell deep into an alcoholic melancholy. He was unpredictable, angry, and so out of control that he was eventually hauled off in a straitjacket. It was at this point that Jalet decided to take the kids and move to Washington D.C. She needed a new life for herself and her children.

Odd Jobs

A year or so later, she moved to New York, where she became a staff attorney on the New York Law Revision Commission. This would be the job she held for a further eight years. She began to develop a keen interest in the Civil Rights movement and by the time her children were grown, she dedicated much of her time to helping those in need. An interesting opportunity soon presented itself.

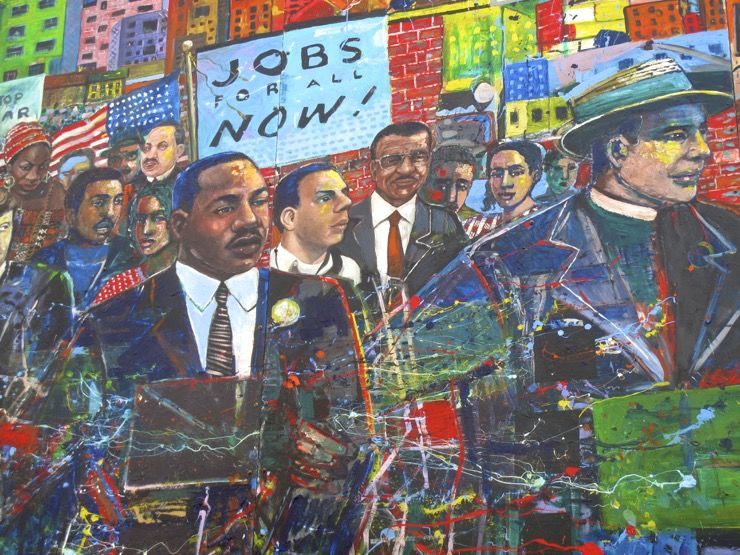

Civil Rights

She applied for and was awarded a Reginald Heber Smith Fellowship, a program generally awarded to attorneys starting their careers. Still, her age made her stand out and before long, she and several others were scattered to poverty-stricken law centers across the country to help those in need. In the summer of 1967, Jalet went to Texas and it was there the 56-year-old met Fred Cruz.

Texas Bound

A week into her Texas job, Jalet received a letter from Cruz who was wondering if she could help him with his case. In all her years as an attorney, she’d never handled a criminal complaint, nor had she even set foot in a prison, but something about Cruz’s words struck a chord with her. Cruz was polite and grateful when she arrived but disappointed when she informed him that she couldn’t officially represent him.

Appeals

Jalet had yet to pass the Texas bar and while she wanted to visit him and help him type up his briefs and rework his case, she couldn’t do much more. Furthermore, she’d only planned to be in Texas until the following June. Cruz graciously accepted any help she could give. Soon, the conversation turned from the law to faith and family. He revealed that he was a Buddhist and she told him that her daughter was studying the “new age” faith. A connection began to form.

Intellectual Connection

Their talks became more and more frequent. Jalet learned about Cruz’s forbidden efforts to educate himself in prison. She learned about how he read the bible, Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialism and Human Emotion, and Martin Heidegger’s German Existentialism. It seemed this convict was more than he appeared.

The Villain

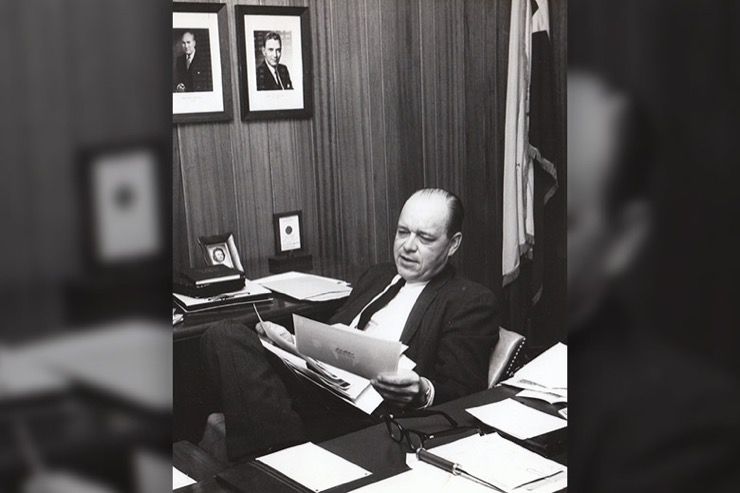

Meanwhile, George Beto, the director of the entire Texas Department of Corrections, was keeping an eye on this strange connection, albeit not a close one. Beto had happened to be visiting Ellis on the day Jalet first met Cruz and seemed rather jovial when he spoke to her, despite his reservations. He was a tall, barrel-chested minister and a self-aggrandizing proponent of his own “successful” prison system.

Powerful Man

Beto warned Jalet to be wary of Cruz, calling him a troublemaker who would invariably con her. She dismissed the comment and he dismissed her as a useless, middle-aged female lawyer. Beto was a powerful man, he controlled a veritable empire 14 separate penal facilities, which held more than 12,000 men and women. As far as he was concerned, she could do nothing to threaten him.

A Living Hell

Even if his charm couldn’t win Jalet over, he could still make Cruz’s life a living hell if she became an issue. He could have him thrown in solitary or remove his lifeline to Jalet. All prisoner’s mail was read and censored, so as soon as their conversations became helpful to Cruz’s cause, Beto cut off their communications. Also, any number of phone calls to his powerful connections would end Jalet’s meddling.

Agitation

By December, Cruz was back in solitary and when he was released, he began keeping notes about his abuse in a diary. The warden found out and came to him with a warning, if he kept writing people about matters that didn’t pertain to his case, he would be put in solitary indefinitely. They believed he was agitating other prisoners and threatened to cut off any visits from Jalet – something they could do since she wasn’t officially his lawyer.

The Ellis Report

Jalet was not about to let this abuse go unanswered. She drafted a document called the Ellis Report, a fifteen-page indictment about how the prisoners in the Texas Dept. of Corrections were being “deprived of their constitutional rights and subjected to a pattern of repression, harassment, and even torture that is shocking. Through abusive practices based on brutality and dehumanization, the ‘inmates’ live in constant fear.”

Terrible Abuse

From her conversations with Cruz, Jalet documented dozens of stories of abuse. She spoke of prisoners being made to stand on a rail, hung from bars in straitjackets, beat with baseball bats, brass knuckles, and blackjacks. There was even an incident involving a prisoner who was made to shell peanuts fore five days straight until he tried to commit suicide by slashing his own wrists.

Show the World

Jalet declared war on the Texas prison system after that. Jalet’s main concerns were the solitary confinement restrictions on prisoners helping one other with legal pleadings were what needed to be challenged in court. The Ellis Report was circulated all over. Jalet made sure it made it into the hands of state agencies and civil rights groups alike even to the NAACP.

Offensive

In the spring of 1968, Beto went on the offensive, but at the same time, Jalet began officially litigating for prisoners’ rights. Texas penal officials organized to sue her, stating that she was fomenting rebellion and even threatened inmates to recant their stories and drop suits. Nevertheless, the attention she brought eventually led to broader prison reform nationwide.

Love and an Ending

In 1972, after he was released from prison, Cruz and Jalet were married. The wedding caused a scandal not just because of their positions but because of their age. She was 61, he was only 32. They remained married for six years until he took up heroin again and the two divorced. Jalet died at the age of 84 in 1994.