Ruth Snyder’s husband, an art editor at Motorboat magazine, had been killed. The grieving widow told police that two giant Italian men had broken into her Queens, New York home and knocked her out. They then proceeded to tie her up in the hallway, steal her jewelry and commit the terrible crime.

Ruth’s 9-year-old daughter was left curiously untouched. Whoever the men were, they were only there for her husband. It seemed even the jewel theft was incidental. Still, something seemed off about Ruth’s story. Something about it smelled funny, the police just didn’t know exactly how funny it really was.

Suspicions Rise

Police were suspicious of Ruth’s Snyder’s story almost from the get-go. For one, she didn’t look as if she’d been knocked out. Then there was her “stolen” jewelry, found stuffed underneath her mattress during a secondary investigation of the home. As if that weren’t enough, there was also the $100,000 life insurance policy she’d filled out mere days beforehand.

Give It Up

A few hours of interrogation saw Snyder spilling her guts about the whole sordid scheme. She quickly gave up the name of her accomplice and lover, a married corset salesman named Henry Judd Gray. According to Snyder, it was Gray who was behind the whole murder. The police picked him up and he too pinned the murder on his accomplice, Ruth Synder.

A Plot’s Plot

As far as Gray was concerned, Snyder had seduced him and coerced him into the deed. It was a confusing situation but made one heck of a story. Think of it, a housewife and a salesman have an affair and then contrive to kill her husband so they can claim the insurance money. It sounds like the plot of a film noir movie, and it would eventually become such a film.

The Real Story

If the obvious insurance fraud weren’t proof enough of how unsuited the two murderers were for such an enterprise, the subsequently released details of the case would certainly hammer that point home. The two lovers had bungled the crime badly from the start with one notable exception: they’d actually succeeded in killing the man they set out to kill.

Bungled

Gray told police that they had killed Snyder’s husband by hitting him with a weight from the window sash. After that, they stuffed a chloroform-soaked wad of cotton up his nose and proceeded to strangle him with wire from a nearby picture frame. All these items were found nearby the body … likely covered in fingerprints.

From The Start

Snyder had wanted to kill her husband almost from the first moment they met. Even though they were engaged to be married, Albert Snyder seemed obsessed and hopefully devoted to his fiancee Jessie Guishard. She had been dead for a decade by that point but he still considered Jessie to be the finest woman he’d ever met – not his new bride.

Loveless

Albert was right of course. Ruth Snyder was cantankerous and irritable. She never loved him, but part of that was because he was so in love with a dead woman. The loveless marriage eventually led her straight into the arms of Gray. Nevertheless, they turned on each other the moment their story about a poorly staged break-in began to unravel.

The Dumbbell Murder

By the time the story made the papers, journalists were already referring to it as the “Dumbbell Murder” by virtue of how foolish the whole plan had been. For the next year, the case received massive media attention. Americans seemed obsessed with it, mainly because those involved were just normal, everyday people like themselves.

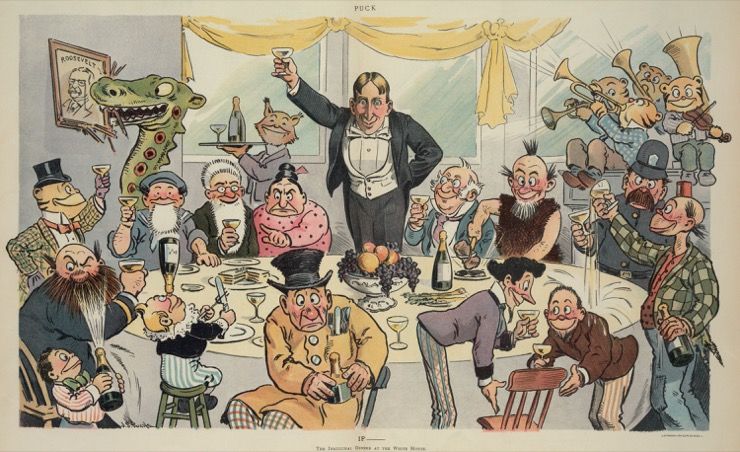

Tabloid Journalism

This was an unprecedented bit of tabloid journalism. It was 1927, a time when the New York tabloid press was at war with one another. The Daily Graphic, the Daily News, and William Randolph Hearst’s Daily Mirror were all fighting to outsell each other. The lurid details already extent in the Dumbbell Murder made it a perfect way to draw more readers.

Sensationalism

Not content with the absurdity already present in the case, the tabloids even started making up details to sell papers. There was no strict adherence to facts at the time or public fallout for providing “fake news.” The tabloid press soon turned Snyder and Gray from bumbling murderers, into cunning criminal lovers straight out of a Hollywood picture.

A Circus

Regardless of the lies, the public ate up every scrap of information on the killer couple. When the trial began, fifteen hundred people packed into the courtroom and another 2,000 wandered about outside. This happened nearly every day. People began selling fake tickets for $50 apiece, while peddlers sold souvenirs and stick pins featuring the sash weight murder weapons.

Femme Fatale

Ruth Snyder went from homely housewife to femme fatale. She was described as a “synthetic blonde murderess” in the tabloids. Ruthless Ruth, the Viking Matron of Queens Village was the real-life version of Chicago’s Roxy Hart. Henry Gray didn’t seem to appreciate her newfound fame, especially since he still alleged her to be the mastermind behind the murder.

Additional “Victim”

Gray also spoke to the tabloids in his own defense. He painted himself as a victim. He described his affair with Snyder saying, “She would place her face an inch from mine and look deeply into my eyes until I was hers completely. While she hypnotized my mind with her eyes she would gain control over my body by slapping my cheeks with the palms of her hand.”

The Book End

The trial ended in several ways, at least in different versions of the story anyway. In James Cain’s novella, Gray’s analog insurance salesmen escapes on a boat to Latin America. He soon discovers his female accomplice had hidden herself on the boat too. Afraid they’ll never be safe, they commit suicide together by jumping overboard at night. The movie tells it differently though.

Credits Roll

The film version, titled Double Indemnity, sees neither of the killers making it out of the country. In this telling, Gray’s salesman kills his girlfriend and ends up waiting for the police to take him away. As morbid and tragic as this Hollywood ending sounds, the real ending to this circus-like tale is even grimmer.

Double Conviction

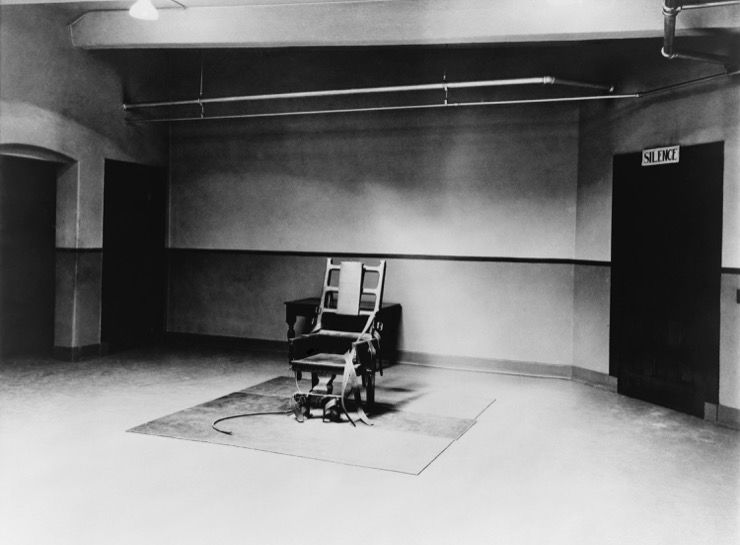

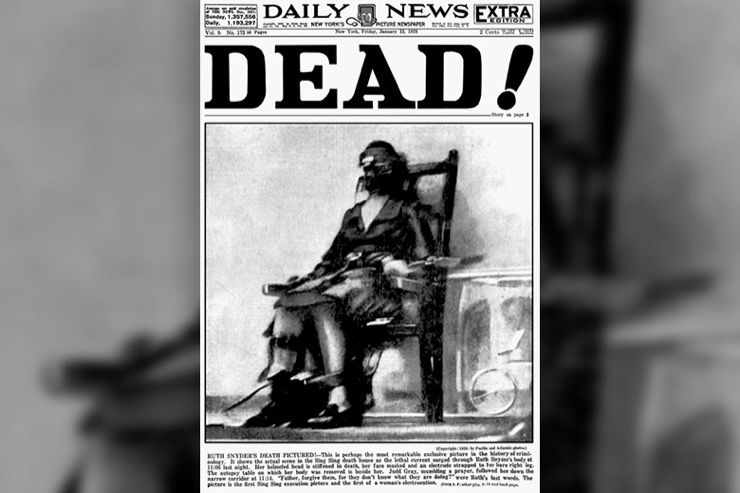

Both Snyder and Gray were ultimately convicted and both of them would die in the electric chair. On the same January day, in fact. Like the rest of the story, the tale of Ruth Snyder’s 1928 execution has its own twists and turns. Sing Sing Correctional Facility allowed no cameras in the room on the day of her execution, but one daring photographer still felt he should try.

Not Allowed

The trial had been a sensation and police knew the execution would no doubt draw just as much media coverage. Photography was of course usually prohibited at executions, but knowing how fervent these newspaper people were, Sing Sing guards were to take this especially seriously for Ruth Snyder. No cameras would be allowed.

Sneaking Into Sing Sing

Newspaper photographer Tom Howard was feeling the pressure when he walked into New York’s Sing Sing Correctional Institution that afternoon. It was a cold January day and as he stepped through the security check and into the execution chamber, Tom couldn’t help but feel a chill wind across the back of his neck. If they caught him, he’d be ejected, maybe even arrested.

Rigged Up

Tom was so nervous because he had a tiny single-use camera strapped to his right ankle. He trod carefully, doing his best to make sure it wasn’t seen and that it didn’t go off. It was a miniature version of a classic camera and the shutter release was wired up his pant leg. The button was undetectable but reachable.

Grim Pictures

The moment that Snyder was electrocuted, Tom Howard lifted his pant leg and pressed the shutter release. He got one good picture of the gruesome scene; a blurry picture of the killer’s bound, masked body shaking from the fatal electricity. The Daily News ran the photo the very next day. The front page headline read “DEAD!” and the paper sold out in a mere 15 minutes.